Question 16

Notice the condition

Question 18

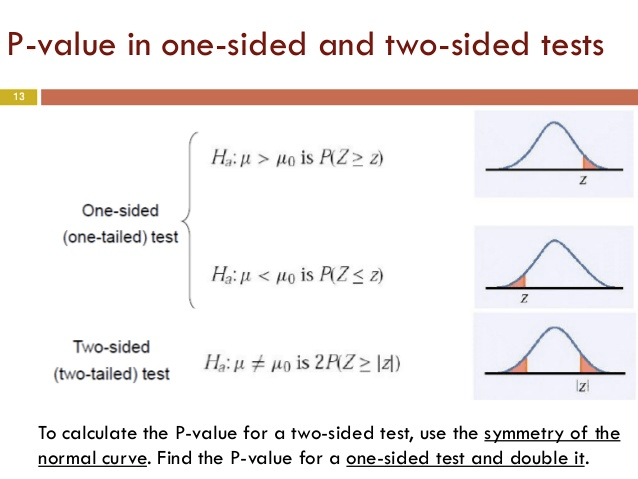

P-value for two-sided t-test = P-value for one-sided t-test * 2

Question 21

Question 25

Question 31

Question 32

H0: There is no association between A and B / Variables are independent

H1: There is an association between A and B / Variables are dependent

P > α

- We fail to reject the null hypothesis and do not have evidence to support the claim that there is an association between A and B

P < α

- We reject the null hypothesis and do have evidence to support the claim that there is an association between A and B

Question 37